Research

Our Research Question

„Does regular storytelling by a professional storyteller further social and emotional competences, creative processes and the development of imagination?“

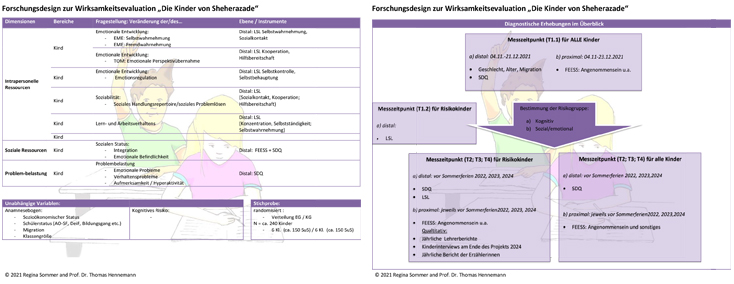

The research design (PDF), developed by Prof. Dr. Hennemann and Regina Sommer

For the quantitative research the following tests were chosen: Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), Teacher’s assessment list of social behaviour (LSL) and Questionnaire on emotional and social school experiences of primary school children (FEESS).

„There once was a boy who could not sit still …“ (pupil no.21, Germany)

Hypothesis I

According to teachers, the regular telling of fairy tales and stories by a professional storyteller leads to a reduction in the psychosocial stress of pupils at increased risk. (measured with the problem-oriented scales of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire; Goodman 1997)

SDQ – Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire

The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) is a psychometric instrument used in child and adolescent psychiatry to assess emotional and behavioural problems in children and adolescents between the ages of 3 and 16. The SDQ is used to recognise psychological abnormalities and social strengths.

The SDQ was filled out by the classroom teacher for each pupil (in the experimental groups as well as in the control groups).

What does the SDQ measure?

The SDQ measures both problematic behaviour and positive skills. It is designed to map various dimensions of emotional and social development. Both strengths and difficulties of a child or adolescent are considered. The questionnaire consists of 25 items, which are divided into five categories (subscales):

1. emotional symptoms (e.g. anxiety, sadness)

2. behavioural problems (e.g. aggressive or oppositional behaviour)

3. hyperactivity and attention problems

4. problems in dealing with peers (e.g. isolation, conflicts with other children)

5. prosocial behaviour (e.g. helpfulness, compassion)

The first four subscales capture the difficulties, while the fifth scale (prosocial behaviour) captures a child's strengths.

Statements that can be made

Based on the results of the SDQ, statements can be made about the likelihood of a child having emotional or behavioural problems. Depending on the score in the various categories, an assessment can be made as to whether the behaviour patterns are normal, borderline or conspicuous.

- Total score for difficulties: The sum of the first four subscales indicates how severe a child's difficulties are overall.

- Individual strengths: The Prosocial Scale provides an indication of the extent to which the child has positive social skills.

Objectivity, reliability and validity

- Objectivity: The SDQ is often completed in the form of standardised questionnaires (by parents, teachers or the children themselves), which ensures a high level of objectivity. The evaluation is based on clear guidelines.

- Reliability: Studies show that the internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha) of the SDQ is satisfactory for most subscales, although some scales (e.g. behavioural problems) have lower values. Overall, the SDQ can be regarded as reliable, although there are differences in accuracy between the subscales.

- Validity: The SDQ correlates well with other established questionnaires that measure psychological problems in children. The instrument has proven to be valid in various cultural contexts and provides a good basis for identifying problem areas. However, its validity is rated as less high for certain diagnoses such as autism spectrum disorders.

Possible confounding factors during implementation or evaluation

There are several factors that can influence the results of the SDQ:

- Subjective judgement: as the SDQ is often completed by parents or teachers, subjective perceptions and biases can influence the results.

- Socially desirable response behaviour: Parents or young people may choose answers that seem more socially acceptable.

- Cultural differences: The SDQ has been validated in different countries, but cultural differences in the perception of behaviour and emotions could influence the results.

- Age dependency: As the SDQ is used for children and adolescents of different age groups, age-related differences in the interpretation of behaviour can distort the results.

Overall, the SDQ provides a good and broadly applicable basis for recording mental health problems in children, but it should always be used in the context of other diagnostic methods to ensure a well-founded assessment.

Results according to SDQ

Due to the different pupil populations, an average value was determined in all tests and a ‘pooled standard deviation’ was calculated. Some graphs appear (at first glance) to be effective or critical, but it is important to consider the effect size.

The Cohen's d effect size is used to assess the size of an effect. The interpretations of Cohen's d are:

→ 0.2: small effect

→ 0.5: medium effect

→ 0.8: large effect

This means that the greater the value of Cohen's d, the greater the difference between the two groups in relation to the scatter of the data.

Hypothesis II

According to teachers, the regular telling of fairy tales and stories by a professional storyteller leads to improved social and learning behavior of pupils under increased risks. (measured using the test procedure Teacher Assessment List for Social and Learning Behavior, Petermann and Petermann)

The LSL was filled out by the classroom teacher for each pupil (in the experimental groups as well as in the control groups).

LSL – Teacher assessment list for social and learning behaviour

The teacher assessment list for social and learning behaviour (LSL) is a diagnostic tool for the systematic observation and assessment of pupils' social and learning behaviour by teachers. It is used to record behavioural problems in everyday school life and is mainly used in primary schools, but can also be used for older pupils. The LSL helps to assess the social and academic development of children, particularly with regard to possible support needs.

What does the LSL measure?

The LSL measures the learning behaviour and social behaviour of pupils in a school context. The aim is to identify possible deficits or strengths in these areas in order to initiate targeted support measures or provide information for educational action.

Categories of the LSL

The LSL consists of two main areas:

1. learning behaviour: This area refers to the way a child learns and cooperates in class. Aspects such as attention, perseverance, motivation, independence and work organisation are recorded here.

2. social behaviour: This area records social interaction in the classroom. It assesses how the child interacts with other children and adults. The central aspects include willingness to cooperate, conflict behaviour, assertiveness and emotional control.

The LSL comprises various items, each of which is assessed on a multi-level scale. Teachers give their assessment of how frequently certain behaviours occur in the child.

Statements that can be made

- Learning behaviour: The results provide an indication of how well a child is able to fulfil school requirements. For example, problems with attention or motivation can be identified.

- Social behaviour: The results provide information on whether a child can work well with other children, resolve conflicts appropriately or shows difficulties in social interaction.

The LSL serves as a basis for taking targeted educational support measures or, in special cases, initiating further diagnostics if serious abnormalities in social or learning behaviour are identified.

Objectivity, reliability and validity

- Objectivity: As the LSL is completed by teachers, objectivity depends heavily on the perception and experience of the respective teacher. There are standardised specifications for evaluation that support a certain objectivity in the assessment. However, subjective perceptions of the teacher can influence the assessment.

- Reliability: Studies show that the reliability of LSL is satisfactory, particularly in the area of learning behaviour. The internal consistency (e.g. Cronbach's alpha) is good for most scales, which means that the items within the scales reliably measure the respective behaviour.

- Validity: The validity of the LSL has been proven by various studies, which show that the teachers' assessments correlate well with other behavioural observation and diagnostic instruments. This means that the LSL actually measures what it claims to measure - i.e. the learning and social behaviour of pupils.

Possible disruptive factors during implementation or evaluation

- Subjectivity of the teacher: As the LSL is completed by the teacher, personal prejudices, the relationship between teacher and pupil or the individual perception of the child can lead to a distorted assessment.

- Context dependency: A child's behaviour can depend heavily on the classroom situation or the form of the day. Disturbing factors such as conflicts in the classroom or external influences could affect the child's behaviour and distort the assessment.

- Limited observation time: Some teachers only see their pupils during certain phases of the lesson, which can limit the opportunities for observation. This could lead to an incomplete assessment of behaviour.

- Social expectation pressure: The assessment of a child's behaviour could be influenced by the pressure to give socially desirable answers or to meet the expectations of the school management or parents.

Overall, the teacher assessment list for social and learning behaviour offers a practical and widely applicable way of assessing pupils' behaviour. It is particularly suitable for initiating targeted support measures, but should always be used in the context of further observations and possibly additional diagnostic tools.

Hypothesis III

The regular telling of fairy tales and stories by a professional storyteller leads to a significant improvement in the social and emotional school experiences of pupils at increased risk.

(measured with the four scales of the questionnaire on emotional and social school experiences of primary school children FEESS 1-2 and FEESS 3-4, Rauer and Schuck 2003; of FEESS 3-4 we used the adapted questionnaire of Prof. Hennemann with his permission)

The FEESS is done by each pupil (in the experimental groups as well as in the control groups).

FEESS – Questionnaire for the assessment of emotional and social school experiences

The Questionnaire for Emotional and Social Experiences at School (FEESS) is a diagnostic tool that aims to assess the emotional and social experiences of primary school children. The FEESS is used to systematically assess children's subjective perceptions of their school experiences and to gain a better understanding of their emotional and social sensitivities in the school context.

What does the FEESS measure?

The FEESS measures the emotional and social experiences of primary school children in the school environment. This includes both positive and negative experiences that children have at school, particularly with regard to relationships with classmates, the behaviour of teachers and their general well-being at school. The focus is on the emotional experience and social interactions at school, i.e. how the children feel at school and how they assess their social relationships.

Categories of the FEESS

The FEESS consists of various scales that are divided into two main areas:

1. emotional school experiences: This domain includes aspects such as school-related happiness, anxiety and stress, self-confidence and general emotional well-being in the school context.

2. social school experiences: This is about the children's social relationships, in particular the relationship with classmates and teachers, the feeling of belonging in the class and possible bullying experiences.

Each of these areas is covered by several items, which the children rate on a scale (usually in the form of ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’).

Statements that can be made

The results of the FEESS provide a comprehensive picture of how the children perceive their school and their social environment there. The following statements can be made based on the results:

- Emotional school experiences: It is possible to record whether a child feels comfortable at school, whether they enjoy school or whether they struggle with anxiety and stress.

- Social school experiences: The questionnaire provides information on how well a child feels integrated into the class community, whether they have positive relationships with their classmates or whether they experience social problems such as bullying.

Analysing the FEES makes it possible to plan targeted measures to promote emotional well-being and social integration, if necessary.

Objectivity, reliability and validity

- Objectivity: As the FEESS is completed by the children themselves, objectivity is largely guaranteed as no external person influences the answers. The evaluation is standardised, which further increases objectivity.

- Reliability: Studies on the reliability of the FEESS show that the internal consistency of the scales is satisfactory overall, with the items in the emotional and social areas reliably capturing the children's corresponding experiences.

- Validity: The FEESS shows good validity, particularly with regard to the assessment of children's emotional well-being and social integration. The validity is confirmed by comparison with other instruments that measure similar constructs. It is also confirmed that the FEESS is able to depict relevant differences between children with different school experiences.

Possible disruptive factors during implementation or evaluation

- Subjective perception of the children: As the questionnaire is completed by the children themselves, the assessment of their school experiences may be influenced by their current mood or by individual events. This could lead to distorted results.

- Comprehension problems: Some children, especially those of lower primary school age, may have difficulties understanding the questions correctly or assessing their emotions and social experiences accurately. This could affect the validity of the results.

- Socially desirable answers: Children may tend to give socially desirable answers, especially if they think that teachers or parents will see the answers. This could affect the reliability of the data.

- Daily fluctuations: Children's emotional and social experiences can be strongly influenced by short-term experiences (e.g. arguments with classmates), resulting in a snapshot that is not always representative of the child's general state of mind.

Conclusion

The FEESS is a valuable tool for gaining insights into the subjective emotional and social school experiences of primary school children. It makes it possible to recognise individual stresses or difficulties at an early stage and to plan targeted educational or psychological interventions on this basis. As with all questionnaires based on self-reporting, the FEESS should be used in conjunction with other diagnostic methods and observations in order to obtain as complete a picture as possible of a child's emotional and social development.

„Listening to stories meant to be without pain.“ (girl, Belgium)

Measuring Instruments

To measure the development of imagination, the instruments are: annual reports of the storytellers (amongst others in regards to develop of pupils’ listening skills), teachers’ questionnaire and interviews with each pupil at the end of the 3-year project.

The Teachers’ Questionnaire

“Listening attentively to stories … being too lively during drawing time.“

“We did a ‘listening comprehension’ test in class, which has never turned out so well.“ (Belgium)

This questionnaire asks the teachers to evaluate the project.

In Belgium there are school grade teachers, meaning grade 1 is always taught by the same teacher. So in our project three teachers filled out a questionnaire.

In Denmark our teacher left after 2 1/2 years and a new teacher took over for the rest of the year.

In Germany the teacher was in the project for all three years.

In Greece each year another teacher and translator accompanied the group.

Questionnaire for Teachers (PDF) »

The filled out forms can be found in Qualitative Results.

The Pupils’ Questionnaires

“It was great fun!“ (boy, Germany)

Here, the pupils were asked about the project and their feelings about the stories in more detail.

We had to develop two different questionnaires. One for Germany, Belgium and Denmark and another for Greece as the study had to be adapted to the specific circumstances of the refugees.

Questionnaire for Pupils (PDF) »

Questionnaire for Pupils Greece (PDF) »

The filled out forms can be found in Qualitative Results.

„The world was grey, with the stories it became full of colours.“ (girl, Germany)

Live Storytelling

With the help of a weekly storytelling session we want to improve or awaken the pupils intelligences or talents.

Comments of children after listening to a live storyteller:

„We were on the stage of life !“ (Kololo Dalcha, 7 Jahre Nigeria)

„It is a film!“ (Ranim, 7 Jahre Marokko)

When Albert Einstein was asked by parents how they could promote their children's intelligence, he replied: "Tell them fairy tales!" What do telling fairy tales and intelligence/abilities have to do with each other? What kind of intelligence is meant? Is it about measuring mathematical-logical and verbal-linguistic intelligence, the two that are recognized and therefore measured and promoted in the current education system? Or did Einstein also mean the development of other forms of intelligence, such as emotional (intrapersonal), musical, spatial, creative, social (interpersonal), a sense of ethics, orientation in the social and physical environment, existential intelligence, intelligence in pattern recognition. Talents that we need for today and tomorrow, if Pablo Picasso had his way. Abilities that may lie dormant in children who we have previously considered to be "particularly in need of support" or who have experienced a different socialization due to their environment.

Why did Einstein say „to tell“ and not „to read aloud“? According to Prof. Dr. Michael Page from the University of Texas, there is a kind of decoding system in the brain that allows for the acquisition and processing of knowledge. He distinguishes between 6 types, mechanisms and ways. These include rhythm, logic, language and movement. Every person has one or two peaks. If the teacher uses these, learning can take place and is even easy. When telling a story, all mechanisms are addressed, so that every listener is able to absorb, understand and process knowledge. If that were true, storytelling would definitely be an enrichment for school lessons.

Objective

Listening to fairy tales promotes talents and thus one's own potential, develops skills, contributes to the development of imagination and creativity, helps with personality development, includes tolerance education, leads to school integration experiences (reducing xenophobic attitudes, exclusion of those who are different) and language acquisition. Storytelling would therefore be an integral part of school classes in socially disadvantaged areas or classes with inclusion.

Procedure

How long would children have to listen to fairy tales to manifest Einstein's claim, among other things? In the opinion of Regina Sommer, who has been working as a professional storyteller in socially disadvantaged schools with long-term storytelling projects for over 25 years, it is a three-year process that consists of two years of listening (input) and one year of telling the story herself (output).

During her 13 years as a storyteller for the Yehudi Menuhin Foundation in the area of the Mus-E project from 1999 to 2012, she was able to gain relevant experience. As an artist, she worked in elementary school classes in socially disadvantaged areas. Here, children of all kinds met each other. Children who had experienced exclusion, children with ADHD, children with learning disabilities, lacking language skills, E-children. Everyone listened to the fairy tales. Here, all disabilities, all problems disappeared. The children listened and then painted their picture. Everyone worked for themselves in the community. As an artist, Ms. Sommer was not bound by any educational guidelines. It was just a matter of respecting the children in the spirit of Menuhin: "… means accepting what is already there, what the child carries within itself, and allowing it to develop and blossom. The gifts, the abilities, the talents that they all have from the beginning and that are too often distorted by our society."

If children listen to fairy tales, myths and fantastic literature every week for around two years, by the third year they will be able to express their own thoughts, develop solutions to seemingly hopeless situations, work in teams, and swap roles in stories and plays on their own. In the children's reflections, approaches and ideas can be recognized from what they have heard, which are then expanded to include new ones. 10-year-old Omar from Egypt, who spent two years in Germany, put it this way: "If you listen to a lot of fairy tales (from the past), you can prepare for the future because you get a lot of ideas!"

Teachers have also found that children's powers of observation deepen, their ability to work in a team, their social interaction, their willingness to discuss and their ability to express themselves increase, and their ability to think in general is stimulated.

„Once upon a time …“

The Stories

For year 1 the tales had to be chosen according to the cultures represented in each class. For year 2 the tales were picked according to the themes of the pupils.

(The initial idea was to publish the tales thus providing a paper or digital version. It was given up as it was not possible to get the approval oft the various publishing houses. At this point we can offer the lists of stories that have been told during the project in the different countries as pdf files.)

Year 1

Albania, Bulgaria, Camerun, Russia, Croatia, Syria, Nigeria, Spain, Afghanistan, Ukraine, Turkey, Vietnam, Irak, Pakistan, Romania, Slovenia, Macedonia, Hungary, South Sudan …

Belgium – List of stories told in year 1

Denmark – List of stories told in year 1

Germany – List of stories told in year 1

Year 2

Ghost stories, tales of angels and devils, fairytales of the Brothers Grimm, animal stories, magic stories, sports, Halloween stories, Christmas tales, giants and witches of the world …

Belgium – List of stories told in year 2

Denmark – List of stories told in year 2

Germany – List of stories told in year 2

Year 3

Pupils as Storytellers

During year 3 of the project the pupils start to invent and create stories of their own. Imagination, a sense of structure and team work manifest themselves in the books and booklets. You can browse through them in Results – Pupils’ Booklets.

Greece

As the children here only stayed for a short time and because the language barrier was very high, the concept of inventing stories in year 3 could not be realized. You can read about the circumstances in the Results – Storyteller’s Reports. Instead, stories were told during all three years.

Greece – List of stories told in year 1

Greece – List of stories told in year 2

Greece – List of stories told in year 3